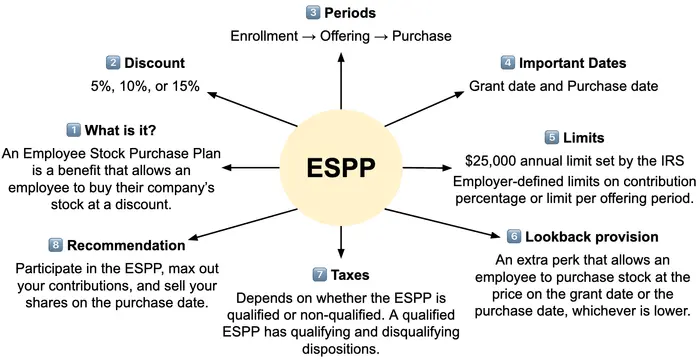

An Employee Stock Purchase Plan (ESPP for short) is a benefit—like a 401k match or an employer HSA contribution—that a company can offer its employees.

An ESPP allows an employee to purchase their employer’s stock, generally at a discounted price of 5%, 10%, or 15%.

Like a 401k match, an Employee Stock Purchase Plan is free money—if your employer offers an ESPP, you should absolutely take advantage of it.

There are some things to keep in mind, however, so let’s have a look at the details.

An example of how an ESPP works

Like anything related to finance, an Employee Stock Purchase Plan involves a lot of jargon.

An ESPP can be qualified or non-qualified. It has an enrollment period, an offering period, a grant date, a purchase period, and a purchase date.

It can also have a lookback provision, and when you sell your shares, there are qualifying and disqualifying dispositions, at a gain and at a loss, all of which have different tax implications.

Rather than defining all these terms now, let’s start by taking a look at an example. We’ll come back to these terms later.

Lexie graduates from Looney Tunes University as a Gag Explosives Specialist and lands a job at ACME Corp. as Head of Road Runner Prevention Inventions with an annual salary of $96,000.

With some quick mental math1, Lexie calculates she’ll get paid $8,000 per month.

She does a happy dance and continues to look through her new hire papers. As she does, one titled ACME’s ESPP Details catches her eye and she pulls it out to have a closer read.

The paper says that ACME offers an Employee Stock Purchase Plan, allowing their employees to purchase ACME stock at a 15% discount.

The paper goes on to explain that the employee is allowed to set an ESPP contribution rate between 2% and 10%, representing the percentage of their salary they’d like to use for the ESPP.

From May to October, the paper says, ACME will take this contribution from each paycheck and set it aside.

Then, on October 31st, ACME will take these six months of contributions and purchase ACME stock with a 15% discount.

If Lexie decided to contribute 10% of her salary, then by the end of October, she’d have contributed $4,800 to the ESPP.2

Let’s say that on October 31, ACME stock was trading at $100.

On this day, ACME would take Lexie’s $4,800, purchase 56.47 shares of ACME3, and transfer them to Lexie.

Without the 15% discount, the $4,800 would’ve only been enough for 48 shares.4 Thanks to the discount, Lexie got an additional 8.47 shares for free! There’s the power of the ESPP.

The next day, November 1st, a new period of the ESPP would begin.

From November to April, Lexie would again contribute 10% of her salary. On April 30th, ACME would again take this money and purchase shares at a 15% discount.

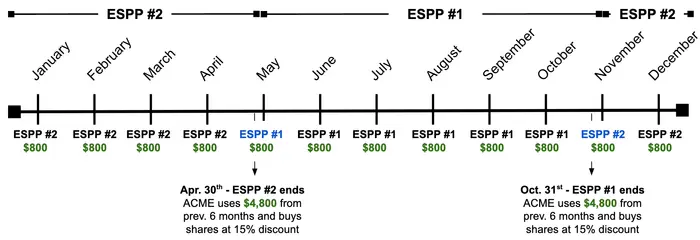

Here’s how this all lines up:

On May 1, ESPP #1 begins.

In May, June, July, August, September, and October, Lexie contributes $800 to ESPP #1. On October 31, ACME takes the $4,800 and buys shares at a 15% discount. ESPP #1 is now over.

The next day, November 1, ESPP #2 begins.

In November, December, January, February, March, and April, Lexie contributes $800 to ESPP #2. On April 30, ACME takes the $4,800 and buys shares at a 15% discount. ESPP #2 is now over.

The next day, May 1, ESPP #3 begins. And so on.

Explaining the jargon of an Employee Stock Purchase Plan

The example above gives a good high-level overview of an ESPP. It’s not too complex!

Now we can come back to the jargon that we skipped over earlier.

An ESPP starts with the enrollment period which is the window of time during which an employee can join the plan.

The enrollment period is followed by the offering period. During the offering period, the employer deducts the employee’s chosen contribution from each paycheck and sets it aside.

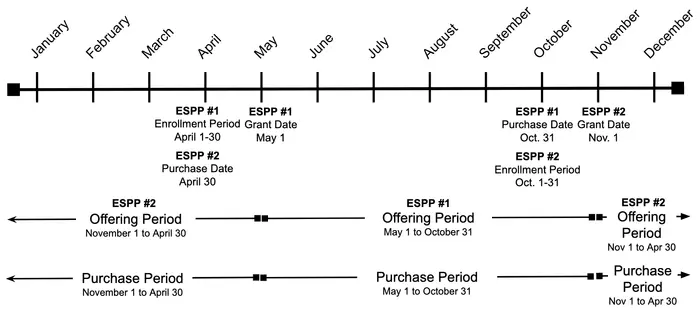

In the above example, ACME Corp. has six-month offering periods that run from May to October and from November to April. The length of the offering period is set by the employer but must be under 27 months5.

Before each of these offering periods, ACME would have an enrollment period. For the May to October offering period, for example, ACME might have an enrollment period that runs from April 1 to April 30.

The length of the enrollment period is also set by the employer. Rather than April 1 to April 30, it could also be a two-week enrollment period from April 1 to April 15—whatever ACME decides.

During the enrollment period, an ACME employee would be able to sign up for the ESPP and set their contribution rate. During the offering period, they’d see the ESPP deduction in each paycheck.

The grant date is the first day of the offering period. Due to this, the grant date is also known as the offering date.

For ACME, this is May 1 and November 1.

The purchase period happens within the offering period. It is generally the same length as the offering period, but it doesn’t have to be—the offering period can be longer.6

For ACME, the offering period and the purchase period are the same, six-month periods that run from May to October and from November to April.

The purchase date is the date when the employer purchases the stock and transfers it to the employee. It is typically the final day of the purchase period and is also referred to as the exercise date.

For ACME, the purchase dates are April 30 and October 31.

If a purchase date falls on a day that the stock market is closed—a weekend or an observed holiday7—the purchase date will be moved to the preceding trading day.

As an example, since October 31, 2026 falls on a Saturday, ACME will move the purchase date to Friday, October 30 instead.

Important Dates for ACME Corp.’s ESPP

| Enrollment Period | Grant Date | Offering Period | Purchase Period | Purchase Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| April 1 to April 30 | May 1 | May 1 to October 31 | May 1 to October 31 | October 31 |

| October 1 to October 31 | November 1 | November 1 to April 30 | November 1 to April 30 | April 30 |

And here it is as a visual:

What are the limits of an ESPP?

We now know how an ESPP works and are familiar with the jargon. Let’s continue by taking a look at the limits of an ESPP.

The maximum an employee can contribute to an ESPP is $25,000 per calendar year. This limit is set by the IRS.8

The $25,000 limit is lowered by the discount offered by the employer.

With a 5% discount, the $25,000 limit becomes $23,750, with a 10% discount, $22,500, and with a 15% discount, $21,250.9

An employer can also decide to set further limits.

ACME, for example, caps the contribution rate at 10%.10

An employer might also set a dollar amount limit per offering period for an ESPP.

In addition to the 10% contribution limit, ACME’s ESPP, for example, might also state that an employee can only contribute a maximum of $7,500 in each offering period.11

An employer might even set a limit on the maximum number of shares an employee can purchase in each offering period.

What is a lookback provision?

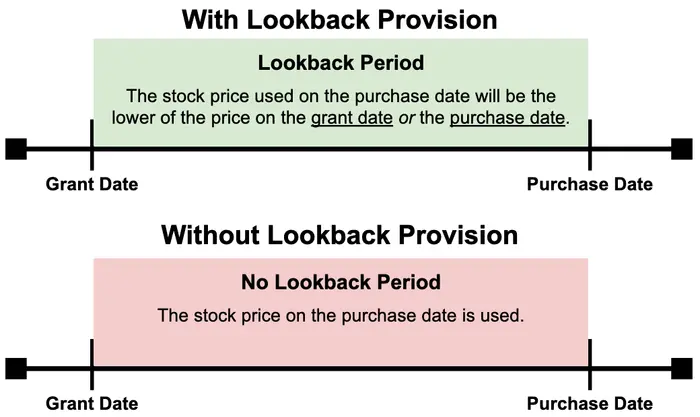

One final feature of an ESPP we haven’t discussed yet is the lookback provision.

A lookback provision makes an ESPP even better.

Instead of using the stock price on the purchase date, a lookback provision allows an employee to purchase stock at either the price on the purchase date or the price on the grant date, whichever is lower.

An example should clear this up.

Let’s say that ACME’s ESPP offered a lookback provision and that ACME stock is trading at $80 on the May 1st grant date.

Fast forward six months to the October 31st purchase date and ACME stock is trading at $100.

Unlike before, when the 15% discount was taken on the $100 stock price on the purchase date, the 15% discount is now applied to the $80 stock price on the grant date, as the stock price on the grant date is lower than on the purchase date.

Without the lookback provision, Lexie pays $85 per share and her $4,800 get her 56.47 shares.12

With the lookback provision, Lexie pays $68 per share and her $4,800 get her 70.59 shares!13 That’s an extra 14.12 shares, worth $1,412.14

So if a company’s stock price goes up between the grant date and the purchase date, the employee will purchase stock at the grant date price.

And if a company’s stock price goes down between the grant date and the purchase date, the employee will purchase stock at the purchase date price.

The lookback provision is a wonderful benefit but sadly not all ESPPs offer it.

Here’s a visual for what an ESPP looks like with and without the lookback provision:

Sidenote

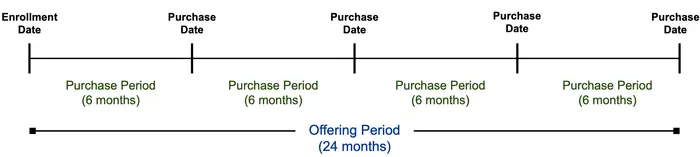

Remember how we said that the purchase period was a subset of the offering period? The lookback provision is why this matters.

Imagine ACME’s plan had a lookback provision and instead of matching six-month offering and purchase periods, they had a two-year offering period containing four six-month purchase periods.

The grant date is the first day of the offering period. This means that on the final purchase date, two years from the grant date, Lexie could be getting to purchase ACME stock at the price from two years back!

If ACME stock had greatly increased during this time, this would be a huge boon for her.

Here’s a visual of what this looks like:

Qualified v.s. non-qualified ESPP

Here’s another twist: an ESPP can either be a qualified15 or a non-qualified plan.

The main difference between a qualified and a non-qualified ESPP is that a non-qualified ESPP doesn’t have to abide by the IRS’ regulations. Due to this, a non-qualified ESPP has less restrictions.

A non-qualified ESPP, for example, can offer a discount larger than 15% and doesn’t have to follow the $25,000 annual contribution limit or be approved by shareholders.

While this might seem like a benefit, the upside of a non-qualified ESPP is limited by the fact that the tax benefit of qualified ESPPs is vastly superior, as we’ll cover in a second.

Companies with a non-qualified ESPP also establish their own limits around annual contributions and discounts and these limits are often lower than those allowed by a qualified plan, further limiting their upside.

While most ESPPs in the U.S. are qualified, non-qualified plans are common in companies that offer an ESPP to their non-U.S. employees as they are simpler to operate.16

How do taxes work for an ESPP?

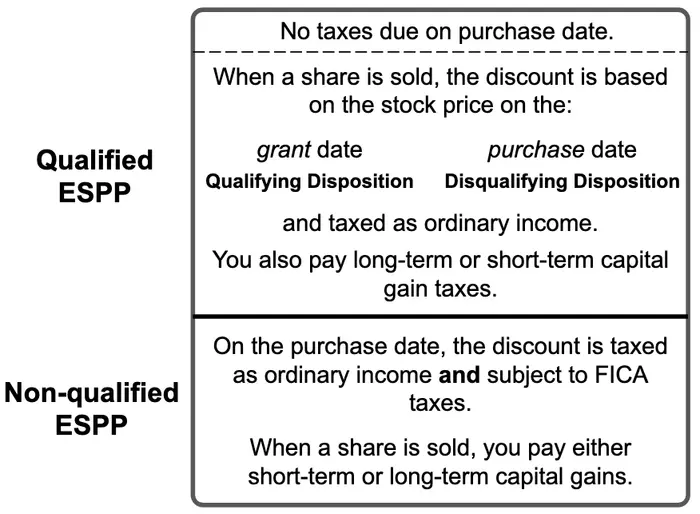

Taxes for a non-qualified ESPP are straightforward. The discount received is taxed as ordinary income, i.e. like salary, and when shares are sold, taxes are paid on capital gains.

Let’s say that ACME’s ESPP was non-qualified.

On October 31, 2023, ACME is trading at $100 and so, after the 15% discount, Lexie’s $4,800 in contributions get her 56.47 shares purchased at $85 a pop.

In total, Lexie received a discount of $847.05. This is the $15 discount per share times the 56.47 shares she received.17

These $847.05 are taxed as ordinary income for that year—just like the rest of her salary—meaning she’ll also pay FICA taxes on this amount.18

When Lexie sells these shares, she’ll pay capital gain taxes. Her gain will be the difference between the price she sells the shares at and the market price–not the discounted price—of the shares on the purchase date.

So if Lexie sells her 56.47 shares for $110, her gain will be $564.70, as she made a $10 gain—$110 minus the market price of $100 on the purchase date—on each share.19

On this gain, Lexie would owe either long-term capital gain taxes20, if she waited over a year before selling the shares, or short-term capital gain taxes21 otherwise.

Taxes are different and slightly more complex for qualified plans.

For a qualified ESPP, unlike a non-qualified ESPP, the purchase date doesn’t trigger any taxes—taxes only come into play when a share is sold.

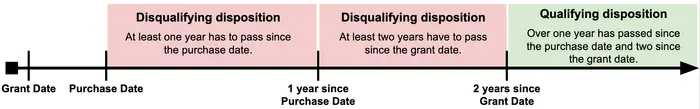

To keep things fun, the sale of a share from a qualified ESPP is characterized as either a Qualifying or a Disqualifying disposition.22

For a sale to be a Qualifying Disposition, two criteria have to be met: two or more years have to pass from the grant date and one or more years have to pass from the purchase date.

Any sale that doesn’t meet both of these criteria is a disqualifying disposition.

Let’s use the same numbers as above and run through some examples in the case that ACME’s ESPP was qualified.

On October 31st, Lexie gets her 56.47 shares and pays no taxes.

If Lexie makes a disqualifying disposition and sells her shares at $110, the $847.05 discount she received is taxed as ordinary income.

Lexie will also pay either short-term or long-term capital gain taxes on her $564.70 gain depending on whether the disqualifying disposition happened before or after a year had passed since the purchase date.

As we can see, the tax implications of a disqualifying disposition are the same as for a non-qualified plan, except that no FICA taxes are paid.

The main difference for a qualifying disposition is that the way the discount gets calculated changes. Rather than the stock price on the purchase date, the stock price on the grant date is used to determine the discount.

This means there are now two cases to look into for a qualifying disposition, the case where the stock price goes up between the grant date and the purchase date and the case where the stock price goes down.

Let’s say that on the May 1st grant date, ACME is trading at $50, and on May 2, 2025, Lexie decides to make a qualifying disposition.

The discount per share is calculated by multiplying the 15% discount by $50—the stock price on the grant date—meaning the total discount is $423.53.23

This is great news! The total discount is lower than in the case of the disqualifying disposition, meaning Lexie will pay less in ordinary income tax.

As before, Lexie will also pay long-term capital gain taxes on her gain. The gain, however, has increased from $564.70 to $3,338.20 as the gain per share is based on the price of ACME on the grant date ($50) rather than on the purchase date ($100).24

As long-term capital gain tax rates are more favorable than ordinary income tax rates, however, she’ll still come out ahead.

But what if on the May 1st grant date, ACME was trading at $150 (instead of $50), and on May 2, 2025, at $200 (instead of $110)?

The discount per share is now $22.5025 (15% of $150), meaning the total discount is $1,270.58.26

This is way bigger than before! Lexie will pay much more in taxes at the higher ordinary income tax rate.

Finally, Lexie will also pay long-term capital gain taxes on her gain. The gain is now $50 per share for a total of $2,823.50.27

This final twist for qualifying dispositions can lead to weird situations where a long-term disqualifying disposition is more favorable than a qualifying disposition.28

Here’s a visual to sum this all up:

Sidenote

As you can see, taxes on an ESPP can quickly get complicated. If you’re looking for more examples, I recommend the article, Taxation of Qualified and Non-Qualified ESPPs.

What should you do with the shares from an ESPP?

There are ten doors in front of you. You have three stickers which you can place on any door. After you place your stickers, a random door will be opened and you’ll get $10 for each sticker you placed on the opened door.

Do you place all stickers on one door or on different doors?

I’d go with three different doors and have a 30% of getting $10 instead of a 10% chance of getting $30.

The analogy isn’t perfect, but when you hold an individual company’s stock, you’re placing all your stickers on one door and betting the house on that company.

Your fates are tied. If they boom, you’ll boom. If they go bust, you’ll go bust.

And boy do companies go bust.

And not only do companies fail often, but the rate of failure is greatly quickening.

In the 1970’s, companies in the S&P 500 had been on the index for 30 to 35 years. This tenure has since decreased to 15 to 20 years.

And when the company you’re betting on is also your employer, your risk is doubled as you would lose your income and savings in a single blow were they to go out of business.

The biggest danger of an ESPP is that you forget about it and end up with a huge chunk of your net worth tied up in your employer’s stock. I’ve made this mistake.

If your ESPP is non-qualified, you’re not getting any tax benefits and should sell your shares as soon as you receive them. You lock in your gain—thanks to the discount—pay your taxes, and move on.

And if your ESPP is qualified, even better. You lock in an even larger gain thanks to not having to pay FICA taxes, sell your shares, and move on.

Is it possible that your profit would be larger if you held on to the shares and made a qualifying disposition to get the more favorable tax treatment?

Is it possible that your company grows like Schwarzenegger on steroids and makes you a millionaire?

Yes, just as there’s a chance that I run a five-minute mile tomorrow morning. (I wouldn’t bet on it.)

By selling immediately, you free up money that you can invest in a total stock market mutual fund, avoid concentration risk in your portfolio, and, most importantly, allow yourself to sleep comfortably at night.

Summary

If you made it this far, you know more about ESPPs than 99% of the population. Nerd-five! 🤓 🎉

Here’s a final visual summarizing this all:

And some final conclusions to wrap things up:

- Qualified ESPPs are better than non-qualified ESPPs as they have a more favorable tax treatment which saves you the 7.65% of FICA taxes.

- ESPPs with a lookback provision are better than those without one. The lookback provision can greatly magnify your gain if the stock price increases during the offering period.

- Holding your employer’s stock comes with significant risk. For this reason, it’s recommended to sell your ESPP shares as soon as you receive them.

I hope this was helpful. Feel free to send me an email if you have any questions.

Stay in touch!

Enjoying so far? Get my posts delivered straight to your inbox each week. 📨

*If this form gives you any trouble, reach out to me at hi@pathtosimple.com and I’ll help you out.

Footnotes

-

$96,000 per year ÷ 12 months in a year = $8,000 per month ↩

-

There are 6 months between May and October—May, June, July, August, September and October.

6 months × $8,000 in salary per month × 10% towards ESPP = $4,800. ↩ -

$100 per share × 15% discount = $15, meaning Lexie is buying ACME stock at $85 ($100 - $15) rather than at $100.

$4,800 ÷ $85 per share (discounted price) = 56.47 shares ↩ -

$4,800 ÷ $100 per share = 48 shares ↩

-

See the IRS regulations around Employee Stock Purchase Plans. You can find the section that mentions the 27 month stipulation with the Google site search syntax.

A non-qualified ESPP, as we’ll cover later on, isn’t subject to this rule. ↩ -

See Adobe’s ESPP is the Best ESPP in Tech for an example where the offering period and the purchase period are different lengths. ↩

-

The New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) and Nasdaq, for example, are closed for 10 holidays—New Years Day, MLK Jr. Day, Presidents’ Day, Good Friday, Memorial Day, Juneteenth, Independence Day, Labor Day, Thanksgiving, and Christmas. ↩

-

See How Do You Calculate the ESPP $25,000 Limit? (or the associated video) for an in-depth look at the ESPP’s $25,000 limit. ↩

-

$25,000 × 95% (5% discount) = $23,750

$25,000 × 90% (10% discount) = $22,500

$25,000 × 85% (15% discount) = 21,250 ↩ -

An ACME employee making $3,000 per month, for example, would only be able to contribute $3,600 per year.

$3,000 per month in salary × 10% (ACME’s maximum contribution rate) × 12 months in a year = $3,600 ↩ -

This means that an ACME employee would have to be making $150,000+ and maxing out their contribution rate to reach the dollar amount limit.

$7,500 per six-month offering period ÷ 6 months = $1,250 per month

$1,250 per month ÷ 10% contribution rate = $12,500 in salary per month

$12,500 in salary per month × 12 months in a year = $150,000 ↩ -

$100 (ACME’s stock price on the purchase date) × 15% discount = $15 and $100 - $15 = $85 (ACME’s discounted stock price on the purchase date)

$4,800 ÷ $85 = 56.47 shares ↩ -

$80 (ACME’s stock price on the grant date) × 15% discount = $12 and $80 - $12 = $68 (ACME’s discounted stock price on the purchase date)

$4,800 ÷ $68 = 70.59 shares ↩ -

$4,800 ÷ $68 - $4,800 ÷ $85 = 14.12

14.12 × $100 (ACME’s stock price on October 31) = $1,412. ↩ -

A qualified ESPP is also called a Section 423 plan as it adheres to regulations established by the IRS in Section 423. ↩

-

Around 79% of ESPPs in the U.S. are qualified. This drops to 50% for companies that offer an ESPP to non-US employees. See GlobalShares.

If you’re in the U.S., your ESPP is likely a qualified plan, but read the FAQs on your employer’s ESPP or ask HR if you’re unsure. ↩ -

($100 - $85) × 56.47 shares = $847.05.

Alternatively, ($4,800 ÷ 85) - (4,800 ÷ 100) = 8.4705 extra shares received due to the discount. 8.47 shares × $100 per share = $847.05 ↩ -

FICA taxes are 7.65%—6.2% for Social Security and 1.45% for Medicare—meaning $64.80 of her $847.05 discount instantly vanish into thin air. ($847.05 × 7.65% = $64.80)

There’s also the 22% Federal supplemental tax rate, so 29.65% of the discount goes towards taxes on the purchase date. ($847.05 × 29.65% = $251.15) ↩ -

$10 × 56.47 = $564.70 or ($110 × 56.47) - ($100 × 56.47) = $564.70 ↩

-

Long-term capital gain taxes are 0%, 15%, or 20% depending on your taxable income. ↩

-

There’s no tax benefit on short-term capital gains as they’re taxed as ordinary income. ↩

-

As covered by Fidelity, disposition is a tax term meaning that one has sold, gifted, or transferred ownership of their shares. It comes from the verb dispose meaning “get rid of by throwing away or giving or selling to someone else”. ↩

-

15% × $50 × 56.47 = $423.53 ↩

-

($110 × 56.47) - ($50 × 56.47) = $3,338.20 ↩

-

15% × $150 = $22.50 ↩

-

$22.50 × 56.47 = $1,270.58 ↩

-

$200 (price on sale) - $150 (price on grant date) = $50

$50 × 56.47 shares = $2,823.50 ↩ -

See Another Scenario for Qualified ESPPs for more discussion on this. ↩